“Stories don’t have tidy beginnings,” says the main character of Heaven’s Vault, outer space archaeologist Aliya Elasra, at the beginning of the game. “The past is always present.”

I was immediately enthralled. I often see people hyper-simplifying history in bad faith and weaponizing it as propaganda, so I was excited to play a game that would expose history’s untidiness and get down in the muck with the ways people uncover, interpret, and rewrite history. For part of its duration, Heaven’s Vault’s heady yarn lived up to its opening and kept me hooked. But as I approached the end, the strings unraveled.

In Heaven’s Vault, an archaeology-based narrative adventure that came out on PC and PS4 today, you play as the aforementioned space-faring raider of tombs, Aliya. You’re tasked by your professor and basically-adoptive mom with tracking down Janniqi Renba, a roboticist from your erstwhile university who has gone missing. At first, Aliya is miffed at the assignment; why send a wayward archaeologist to hunt down a human being who’s ostensibly still breathing and not even close to a piece of ancient pottery? It quickly becomes apparent, though, that Renba has left a breadcrumb trail of ancient artifacts in his wake, all of which portend a grim future for a universe that has forgotten its past.

That’s a bummer for them, both in that a) everybody in this world is gonna die, and b) they’re all missing out on some really interesting history! The world of Heaven’s Vault is as intricate as any of those old Grecian urns that all the kids have been known to write odes to. It’s a ramshackle society reliant on ancient technology that has been stacked on top of a ruin stacked on top of countless older ruins stacked on top of a wellspring of intrigue. A series of outer space rivers span disparate planets, and only the truly bold—yourself included—dare to sail them.

Many of the residents of the wealthy, powerful, and more than a little oppressive moon of Iox think those outer space rivers are tied to a concept they believe in called The Loop, which is an eternal cycle of history repeating itself, complete with the same rises and falls. While your mentor, who lives on Iox, is All About That Loop, Aliya is extremely skeptical of her university’s dominant scientific theory/religion. She believes history is a tangled mess that must be studied and understood to inform the present, not to predict some neatly-packaged future that’s allegedly about to happen again and that just so happens to threaten the people in power.

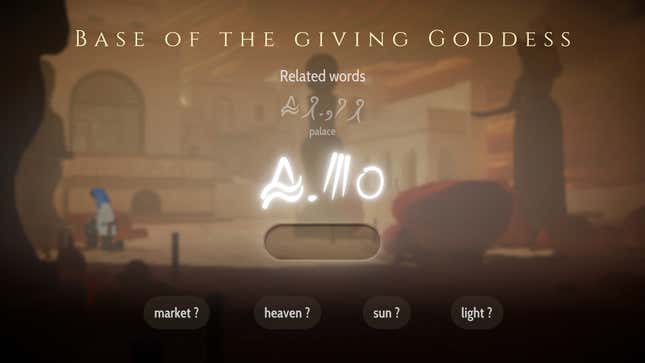

Aliya’s search takes her to a series of progressively more ancient sites in which she scrutinizes artifacts that contain snippets of a lost language. She has to translate these swirly-whirly runes using context, translations of previous runes, and no small amount of guesswork. This is where Heaven’s Vault shines brightest. Using scraps of language to create a patchwork quilt of historical happenings is a thrill—a slow-paced thrill, but a thrill nonetheless.

Initially, all you can do is take stabs in the dark with runes that are, thankfully, sometimes pictographic. Later on, you might find, say, a sword whose etching contains a word that you discovered on a door frame earlier, which confirms the meaning that you previously had only guessed was correct. That word’s meaning is then set in stone, and it feels goddamn fantastic. This only gets better with time, as you learn the ins and outs of the language and start to make more educated guesses. Heaven’s Vault is full of tiny revelations; I never would’ve thought one of my favorite gaming moments of the year would be realizing that a particular symbol denoted the past tense, but here I am.

These discoveries go into a massive timeline that spans the whole of history as you (and Aliya) now understand it, from the beginnings and ends of barely-understood eras, to what you did on the most recent planet you set foot upon. You can zoom in and out of this timeline whenever you want and re-translate old phrases. It’s a sleek, handy feature that helps you keep up with the game’s constant trickle of new information. That would all be tough to keep straight in your head without this tool, because, again, it spans thousands and thousands of years.